For 95 years, the Rotary Club of Las Vegas has helped build a city that transcends showgirls, celebrities, and slot machines

Bright lights, big heart

Two weeks before Christmas, Santa Claus hangs a left on Tropicana Avenue and drives toward a mall, shielding his eyes from the desert sun. He passes a cactus festooned with holiday lights and, as he walks into J.C. Penney, shouts, “Ho, ho, ho!” to children rubbing their hands together for warmth. The temperature? A frigid 55 degrees.

Dressed in shirtsleeves and a battery-powered Santa hat that flops back and forth on his head, Old St. Nick bears an uncanny resemblance to Jim Hunt, an insurance executive who runs the annual Santa Clothes program for the Rotary Club of Las Vegas. Each year the program sponsors shopping sprees for underprivileged children. Hunt built the program from 35 grade school students in 1996 to 365 today.

Fremont Street, aka Glitter Gulch, 1952

Photo by Edward N. Edstrom

Inside Penney’s, scores of excited children fan out through the aisles. “Happy shopping!” exclaims Santa Jim as the kids run out of sight.

Each child has a guide to help find the right coat or shoes. Jennifer, 17, helps a first-grader try on an Avengers T-shirt. “It’s so fun being on the grown-up side of things,” Jennifer says, beaming. Ten years ago she was a Santa Clothes kid herself, picking out shoes, jeans, and a blanket decorated with teddy bears. “I’ve still got the blanket. Now I want to help kids who need it like I did.”

Club President Michael Gordon stands by a cash register. Each kid has a $200 spending limit. “We want them all to get as close to the limit as possible,” he says. “It’s a bit of a crapshoot to see who comes close without going over.” And if anyone goes over $200? “Well, we pay it.”

A sturdy fellow with black hair and a stubbly goatee, Gordon speaks with a slight South African accent. He came to Las Vegas as a Rotary Ambassadorial Scholar in 2006. “I couldn’t believe my good fortune, but didn’t know what to expect in Nevada,” he says. “No one in my family had ever been to the States. But people said it got cold in America, so I came prepared.” He walked out of McCarran International Airport wearing a winter parka.

The parka hung in a closet while Gordon earned a Ph.D. in public affairs at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV). He’s now director of strategic initiatives and research at the Las Vegas Global Economic Alliance, working to speed the city’s growth. “It’s an exciting time for Las Vegas,” he says. “We’ve got the Raiders moving here from Oakland in 2020. There’s the Hyperloop, a high-speed train that might get people here from Los Angeles in half an hour. We’ve got a new WNBA team, the Aces; the beginnings of a driverless bus system; a new bar where robots serve drinks; and plans for Interstate 11, which could one day go all the way to Seattle.”

Gordon laughs. Civic pride is in his blood – as is Rotary. His father, George, is president of the Rotary Club of Bellville, South Africa. “Father-and-son presidents 10,000 miles apart,” Gordon says. “That’s probably a first. We compare notes, but there’s no rivalry.”

George Gordon is proud of his son’s achievements. “Michael’s club has 137 members to our 26,” he explains via email. “We don’t have the finances to pursue as many major projects, but we do what we can. And of course I look forward to visiting his club in Las Vegas.”

Who wouldn’t? The club is pretty much like any other – except for the prime rib at meetings, casino chips in the End Polio Now piggy bank, celebrity visitors, and pirate ships outside the holiday party. And topping all that: the club’s ambitions.

The First State Bank and Kuhn’s Mercantile in 1905, the year Las Vegas was founded.

Photo from Elbert Edwards Collection/University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Eighteen businessmen founded the Rotary Club of Las Vegas in 1923. They included founding President Les Saunders, manager of the local Chamber of Commerce, as well as two bankers, two haberdashers, a butcher, a doctor, a pharmacist, an auto dealer, the town’s only dentist, and several Union Pacific railroad executives. “They were the men who built this city as a community, not just a gambling mecca,” says Michael Green, an associate professor of history at UNLV. “A real city needs bankers and businessmen, not just casinos.”

In those days, Las Vegas was a busy if sparsely populated (2,304 residents) railroad crossing. But after 1931, when Nevada legalized gambling and construction began on the Hoover Dam, the town gradually morphed into Sin City, the country’s capital of legal vice and quickie divorces. During the 1950s, with the construction of nearly a dozen hotel-casinos on the Strip, it boomed like the atomic bombs the military tested in the desert 65 miles northwest of town. By 1960, the population had grown to 64,405. Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack yukked it up at the Sands, soon followed by Elvis Presley, who put the viva in Las Vegas.

Cy Wengert, in hat, a charter member and president of the Rotary Club of Las Vegas.

Photo from Wengert Family Collection/University of Nevada, Las Vegas

Through it all, casino operators and business leaders, some of them Rotary members, worked together. One Rotarian’s off-hours tasks included carrying bags of silver dollars from casinos to a mob boss. When there were too many bags to fit in his car, he switched to a limo, then to a truck. Another Rotarian dreaded meetings because the club fined members who got their names in the paper – and he had been indicted for skimming casino cash. (A bum rap, his lawyer said.)

“Gaming was legal,” says Green. “A businessman didn’t need to know where a client got his money. One thing that meant was that mob money not only paid for much of the city, it served many good ends. You might go to someone like Bugsy Siegel and say, ‘We’re raising money for a great cause. We need free use of your ballroom and $3,000.’ That’s in everyone’s interest.”

The Las Vegas Rotary Club met in showrooms at the Stardust, Harrah’s, and the Desert Inn. Fines for being late or forgetting your Rotary pin started at $100. “Everything’s bigger in Vegas,” says Bob Werner, a longtime florist whom the stars called whenever they needed a floral horseshoe or a car full of roses. “It’s a good florist town,” he reminisces. “Diana Ross naturally needs more flowers in her dressing room than Céline Dion, and Céline needs more than Diana. I did OK. Now I enjoy going to meetings at the best club in the world.”

“I think it helps that we’ve got a chip on our shoulder,” says Randy Campanale, one of a dozen past presidents who play active roles in the club. “When people call us Sin City, it makes us want to prove we’ve got good people here.”

Last fall, a gunman perched in the Mandalay Bay hotel killed 58 people and wounded 422. Within hours, Gordon was phoning the past presidents, men and women he relies on as trusted advisers. He had one question: “What can we do?” The club arranged to pay for needy victims’ funerals.

It was only the latest of its many causes, which include food and blood drives, tuition grants, and awards for exemplary soldiers at Nellis and Creech air force bases, key employers in Clark County. Gordon also wants to bring in a Junior Achievement BizTown, a kid-size city where grade school students play everything from chief financial officer to mayor to intrepid reporter.

These days the club meets on Thursdays at Lawry’s the Prime Rib on Howard Hughes Parkway. Members pay $30 for lunch. Over the years they’ve heard speeches from show business celebrities – such as Debbie Reynolds and Louie Anderson – as well as Las Vegas Mayor Carolyn Goodman, and her husband, former mayor (and mob lawyer) Oscar Goodman; boxing promoter Bob Arum; and Jerry “Tark the Shark” Tarkanian, the towel-chewing basketball coach of UNLV’s NCAA champion Runnin’ Rebels. With an annual budget of almost $500,000 and a local foundation fund that spins off more than $50,000 a year in interest, the club has resources few can match. And the money’s legit: Las Vegas, perennially one of America’s fastest-growing cities, got respectable long ago.

“I love what they’re doing here,” says District 5300 Governor Raghada Khoury. “They’ve got a club for new members, the 25 Club, that gets them off to a flying start.” (In Vegas, new arrivals spend two years in the 25 Club, proving they’re Rotary ready, before graduating to full membership.) “They’ve got Rotaract, Interact, even Kideract for grade-schoolers. They’ve got a car show, foundation giving, PolioPlus, on and on. Smaller clubs don’t have the resources to do all that, but any club could pick one of these projects and do it well.”

As it did with Jennifer, the 17-year-old Santa Clothes guide, Rotary made an early and indelible impression on Khoury. She remembers a Rotary program that brought books to children in Yonkers, New York. “I was one of those kids,” she says. “I became an avid reader thanks to those books.” As an adult, she got off to a rough start at a Rotary club in Southern California: “We were the first district ever to admit women – and the men wouldn’t talk to me!”

She decided to quit Rotary, but the club president urged her to give it another try. “I threw myself into it,” says Khoury, who rose to president and finally district governor. Since last year she has put 28,000 miles on her car, driving from club to club in California and Nevada, promoting causes such as satellite clubs that meet twice a month. “I’m for ideas that can increase retention of the members we’ve got and bring new ones in,” she says. “My message is: Don’t just show up at meetings. Roll up your sleeves and be a real Rotarian.”

The 2017 Santa Clothes shopping spree.

Photo from Las Vegas Rotary Club

From the Santa Clothes event, Club President Gordon drives to a football field on the UNLV campus. The 300-plus kids have finished their shopping sprees and are running races with the university’s track team, hitting Wiffle balls with its baseball players, knocking down foam tackling dummies with football players, and doing jumping jacks with Runnin’ Rebels cheerleaders.

“This is life-changing for them,” says Katie Decker, who runs three elementary schools with busy Kideract programs. (Gordon calls her “Rotary’s favorite principal.”) Decker’s students learn The Four-Way Test, which is painted on her schools’ walls. Once a year, the Kideract kids attend a club luncheon in their honor. “We let them run the meeting,” says Gordon, who last year stepped aside for a Kideractor half his size.

Gordon’s next stop is the local PBS station, KLVX, where Past President Tom Axtell helped build the state’s only interactive library for deaf and blind children. Another of Axtell’s projects was higher-tech, and it has assumed an even greater significance since the October shootings. “We digitized the blueprints of all the school buildings in Las Vegas, as well as contact info for thousands of school employees, students, and parents,” Axtell explains. “If there’s a lockdown due to a terrorist event or any sort of disaster, we embed all that data in our TV signal. Viewers can’t see it on the screen, but emergency responders get it instantly.”

From the TV station, Gordon heads to the city’s sprawling Salvation Army complex. Maj. Randy Kinnamon shows off recent shipments of wheelchairs and food the club has donated. Gordon shakes hands with a once-homeless chef named Jeremy – his specialty is braised short ribs – who now prepares more than 1,000 Rotary-subsidized meals a day.

And then it’s back to the Strip, where pirate ships circle the social event of the year.

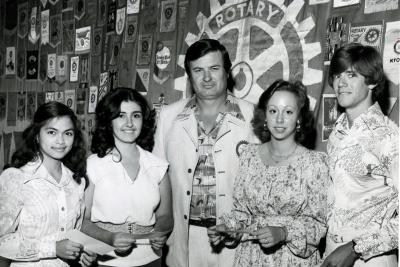

President David Welles and 1976 Rotary high school scholarship winners.

Photo from the North Las Vegas Library Collection/University of Nevada, Las Vegas

The ballroom at the Treasure Island Hotel and Casino features a deejay, balloons, giant snowflakes projected on the walls, and a theater-size movie screen showing photos from past Santa Clothes sprees. The club’s holiday party owes its youthful vibe to more than the kids on the screen. Jimmelle Siarot, a mother of three who works the front desk at the Flamingo, greets attorney Anna Karabachev, 28. They came up from the 25 Club with entrepreneur Erik Astramecki, 27, who moonlights as a mixed martial arts fighter.

Not long ago, Astramecki provided one of the only-in-Vegas scenes the club is known for. “The whole Rotary club,” he recalls, “came to my first big fight,” which was staged within the eight-sided fighting cage at the Cannery Hotel & Casino. Prefight, as Astramecki psyched himself up inside the Octagon (as the fighting cage is called), the national anthem began – and then the PA system conked out. “Total silence,” says the pugilist, “till the Rotarians picked up the song. Pretty soon we’re all singing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ a cappella.”

Gordon enters the Treasure Island ballroom to scattered applause. Dressed in a kilt to honor his Scottish ancestry, he smiles and bows as some club members sing “Happy Birthday to You.” The aging president, as he calls himself, turned 40 today.

“There’s a lot to celebrate,” Gordon says, posing for pictures with his wife, Amanda.

“We’re expecting,” Amanda adds. District Governor Khoury pins a button on the expectant mother’s waistband. It reads “Future Rotarian.”

From the stage, Gordon introduces Jackie Thornhill, who is slated to be president in 2019-20. Then he assesses the biggest fine of the year: $9,500 to a member who had gotten engaged and gotten his name in the paper. Of course, the club’s famously high fines are all for show: Offenders usually bargain their way down to $5 or $10.

After a dinner of shrimp, steak, and cake, the deejay cranks up the music. Michael Gagnon, wine buyer at the MGM Grand, dances with private investigator Arleen Sirois. Several other members pull Gordon to the dance floor. He resists at first. Fifteen hours into his workday, he looks tired. But the room is thumping as Bruno Mars belts out “Uptown Funk.” After a moment the burly, kilted Gordon throws his hands in the air. He spins and boogies for all he’s worth – no hip-shaking Elvis, but not bad for a zealous urban planner and indefatigable Rotary dad-to-be.

-- Kevin Cook is a frequent contributor to The Rotarian. His latest book is Electric October

• Read more stories from The Rotarian