Classrooms wired for success

To close the digital divide in Panama, they started with the teachers

It began, in Panama, with a simple backpack drive.

The Rotary Club of Panamá Norte loaded the packs with essential supplies and distributed them to grade schools throughout the country, a classic Rotary service project repeated in communities around the world. In this case, though, it led to something extraordinary — momentous changes in Panama’s education system.

The spark that ignited it came from what the Rotary members witnessed while delivering those backpacks about 10 years ago. “One of the things that we saw was the disaster in terms of technology and in terms of the possibility of kids being able to learn with technology,” says club member Enedelsy Escobar-King. “Most of the time what we found was that all of the computers were destroyed, or they were to be discarded, or that teachers didn’t know how to use them.”

Over the next few years, club members continued to deliver backpacks but also laid the groundwork for a larger project to address the high-tech disaster they had encountered. Specifically, they turned their attention to two grade schools in Veracruz, a corregimiento (or township) about 10 miles southwest of Panama City, where the club is based.

Gwen Keraval

Working with the Rotary Club of Westchester (Los Angeles), the Panamá Norte club put together a global grant that received $72,000 from The Rotary Foundation, District 5280 (California), the club itself, and other sources. Among other things, it provided each school with 30 laptops for students; a smart, interactive whiteboard to digitize classroom presentations and tasks; and all the auxiliary hardware and furniture required for a high-tech, 21st-century classroom. To ensure the project’s success, the grant also provided for extensive training of school staff and community leaders.

The club launched the project in 2018, and the new equipment and opportunities for learning were immediately embraced by teachers and students. At the end of the 2019 school year, the project had, by all appearances, been a success. One of the schools that participated was even chosen to take part in a countrywide academic competition, a first for the school and, despite failing to win, a laudable achievement.

Yet an unexpected problem arose. “The teachers that we had trained for the interactive classrooms were rotated out,” a regular practice in Panama’s public schools, says Escobar-King. “And the teachers that were new didn’t have a clue about technology. We had to start all over again and try to train those teachers. When we got that setback, we said, well, let’s find a more permanent solution.”

For Escobar-King and the rest of Panamá Norte, class was back in session.

Escobar-King — she goes by “Nelly” — joined the Rotary Club of Panamá Norte in 2015 after a long career with UNICEF. Some projects she worked on with UNICEF were related to education, so when she retired and returned to Panama, she knew she wanted to remain involved in that area.

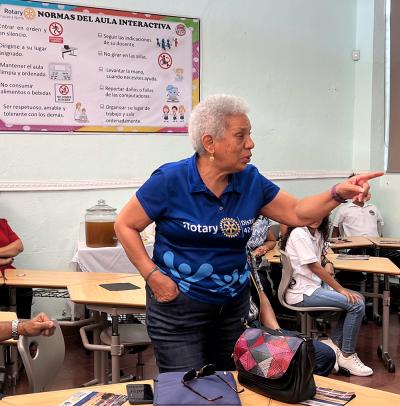

Enedelsy Escobar-King addresses students in the digital classroom of a participating elementary school.

Regina Fuller-White

Escobar-King was motivated, in part, by the dire state of primary education in Panama. She points to the results of the exams known as the Programme for International Student Assessment that are conducted by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. In the most recent results, Panama ranked 75th in science and 76th in math among 78 countries and geographic areas and 71st (out of 77) in reading.

With that in mind, as well as the unexpected development of the teacher shakeup in Veracruz, the Rotary Club of Panamá Norte posed an important question: “How can we get teachers already trained so that no matter where they are sent, they already have the technological tools they could use?”

The answer turned out to be quite simple: Want to get teachers trained? Go to the teachers’ training school — in this case, the Normal School in Santiago, about 150 miles southwest of Panama City. “It is the main teaching college in Panama,” says Escobar-King, “and it’s going to produce the future teachers of the country. As part of the curriculum, would-be teachers have to teach in a real classroom. So we said, OK, let’s make sure they do it in interactive classrooms.”

Working with the Rotary Club of Kansas City-Plaza in Missouri, as well as other clubs in Panama, the Panamá Norte club applied for and received a global grant of more than $230,000 for what they called the Paul Harris Interactive Digital Classrooms. Six of the classrooms would be installed at the Normal School, and another classroom at each of the two nearby grade schools where the apprentice teachers would do their in-class training.

This time, the grant would again provide the high-tech equipment needed for the classrooms. But the emphasis was elsewhere. “The most important component was not just to train the teachers to use the equipment but to teach them innovative methodologies that use the technology to teach the kids in schools,” says Escobar-King. “And that’s how the principles of this particular project were developed.”

Students in the Rotary-sponsored digital classrooms showed a higher level of engagement.

Enedelsy Escobar-King

From the beginning, the project was a model of collaboration among Rotary members, the Normal School, Panama’s ministry of education (Meduca), the Universidad Tecnológica de Panamá, and the Normal School’s parent-teacher association. Lessons learned from the Veracruz experiment were invaluable as the project in Santiago took shape.

Escobar-King also singled out the Basic Education and Literacy Rotary Action Group (whose board she serves on) and the Rotary Foundation Cadre of Technical Advisers. “They are valuable Rotary resources,” says Escobar-King, “and we have a very close working relationship with them.”

For help in designing the curriculum, the Panamá Norte club turned to the Universidad Tecnológica de Panamá, which put them in touch with Dillian Staine, a professor at the Universidad Latina de Panamá. He designed the curriculum with both the future teachers and the teachers leading the Rotary-sponsored classes in mind, There were, however, some complaints about the rigor of the course. “It is quite an intense course,” Escobar-King acknowledges. “But we don’t want to reduce the quality of the course. We would rather help prospective teachers reach that level of learning.”

Not only will the Santiago project enhance the abilities of those teachers at the Normal School but it will have what its creators call a “multiplier effect.” According to the calculations laid out in the global grant, each teacher, once graduated and posted in a school, will have 30 students in a classroom. Over just one year, that means that as many as 2,500 students would be beneficiaries of the project.

What’s more, those newly posted teachers will have the opportunity to train other teachers at their new schools in the innovative digital teaching techniques they learned at the Normal School. And, of course, the Normal School will continue to train other upcoming teachers in the Paul Harris Classrooms, which Meduca has agreed to oversee.

At press time, Panamá Norte, working with Meduca, the Rotary Club of Las Vegas WON, and other clubs in Panama, was preparing to submit an application for another global grant. If approved, it would provide funds three times greater than those awarded to the Santiago project and allow the digital interactive classrooms to expand across Panama. “We are very committed to the project,” says Escobar-King.

Panama’s future may well depend on that.

This story originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of Rotary magazine.