The Rotarian Conversation:

Denis Mukwege

As a doctor, this Congolese physician cares for women brutalized by sexual violence; as their champion, he cries out for justice. His efforts nearly cost him his life — and earned him a Nobel Peace Prize

Denis Mukwege has talked about the horror of rape hundreds of times. He has testified in front of the United Nations, the European Parliament, and the U.S. Senate. He has given countless interviews to journalists and filmmakers, spoken at events for doctors, politicians, and laypeople, and trained other doctors to perform the lifesaving gynecological surgeries he’s famous for.

Despite all that, the Nobel laureate sometimes finds himself struggling to describe the terrible things he has witnessed. Last May, Mukwege, 64, sat down with The Rotarian to discuss his decades working in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and at one point words failed him. “If you can rape a grandmother who is 80 or 90 years old ...” he began before his voice trailed off into silence.

Mukwege’s graphic accounts — and be forewarned, they are gruesome — come from the front lines of Congo’s ongoing conflict, “arguably ... the world’s deadliest crisis since World War II,” according to a 2008 report from the International Rescue Committee. The report estimated that between 1998 (the beginning of the Second Congo War) and 2007, an estimated 5.4 million people died as the result of the violence. More than 2 million of those deaths occurred after the war technically ended in late 2002, as armed groups and militias continued to fight, perpetrating hideous and premeditated acts of sexual violence on innocent women and children.

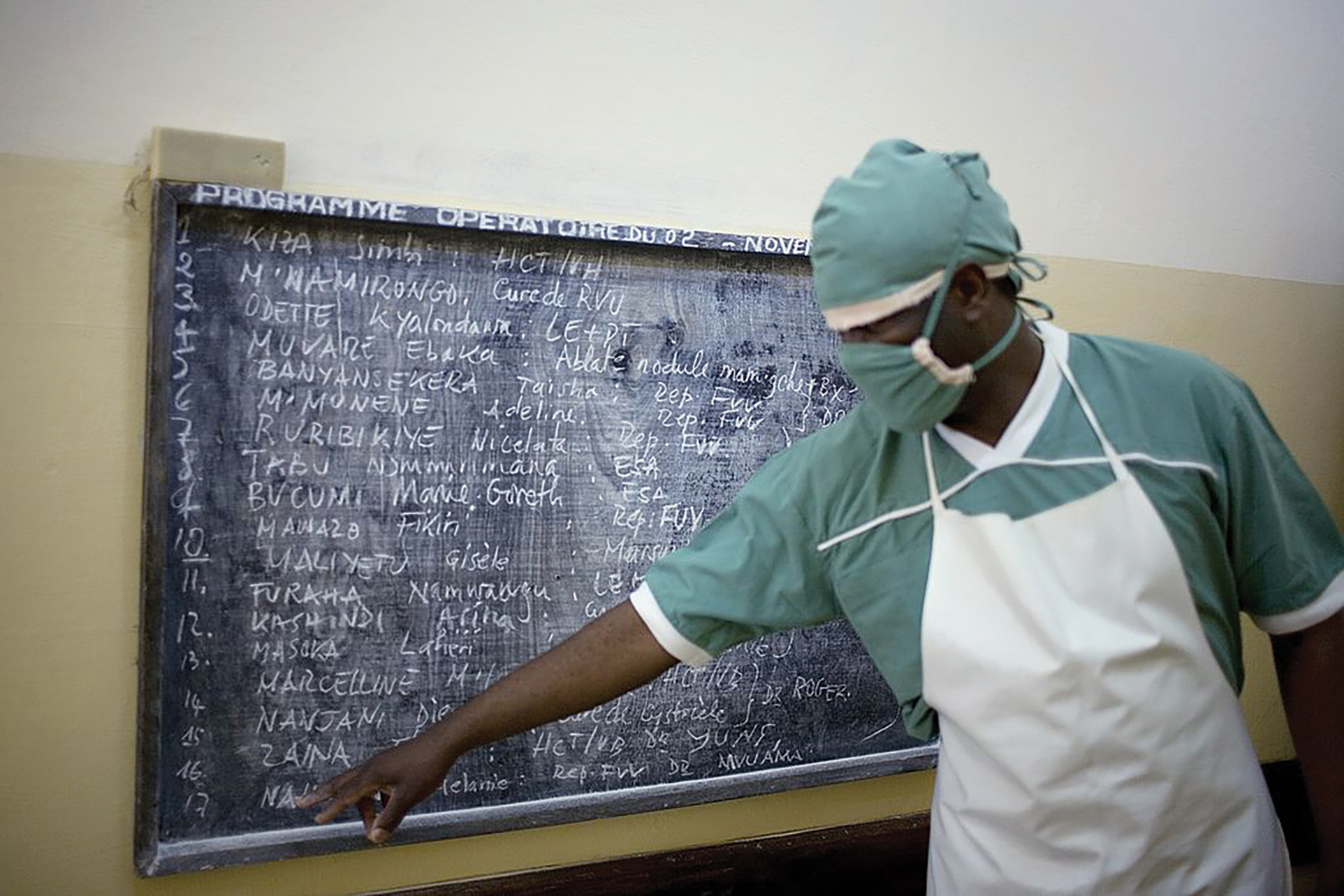

In 1999, when he founded Panzi Hospital in the hilly outskirts of his birthplace, Bukavu — a city in eastern Congo that bumps up against the border with Rwanda — Mukwege intended to concentrate on reducing maternal mortality. That illusion didn’t last long: His first patient needed multiple surgeries after being raped and shot point blank in her genitals. He soon understood this was not an anomaly: Within three months, he had treated 45 women who had been raped, their genitals shot, burned, or sliced with bayonets. “At the beginning, I could not believe that a human could do these kinds of things to another human,” he says. “It was shocking to me.”

In 2010, a UN special representative called Congo “the rape capital of the world,” an epithet validated by another study — this one published in 2011 in the American Journal of Public Health — which estimated that 400,000 women in Congo were raped over a 12-month period in 2006-07. Over the past two decades, Mukwege’s Panzi Hospital has treated more than 50,000 victims of sexual violence.

Fueling this violence are ethnic tensions and a struggle to control the untapped riches that lie buried in the impoverished but mineral-rich eastern Congo. During the interview, Mukwege pointed the finger at one culprit in particular: coltan, a dull, black metallic ore (technically, columbite-tantalite) that’s an essential component of cellphones, laptops, and other electronic gadgets.

Mukwege began delivering speeches around the world about the problems in his country. In September 2012 at the UN, he excoriated Congo and the international community for lacking the political will to “arrest those responsible for these crimes against humanity and to bring them to justice.” A few weeks later, he survived an assassination attempt in Congo that left his security guard dead. Mukwege moved with his family to Belgium; he returned to Bukavu and a hero’s welcome in January 2013.

In 2018, Mukwege shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Nadia Murad, a young Iraqi woman held in sex slavery by ISIS before she made a nighttime escape; the Nobel committee saluted them “for their efforts to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war and armed conflict.” Mukwege dedicated his prize to “women of all countries bruised by conflict and facing everyday violence.”

When they heard the news, “the patients and staff were singing and dancing and shouting out of joy and happiness all over the hospital,” says John Peter Mulindwa, a doctor at Panzi and a member of the Rotary Club of Bukavu Mwangaza. “The prize has impacted our everyday work. Everyone as a team is motivated and encouraged.”

Mukwege spoke with senior staff writer Diana Schoberg after his speech at the Rotary Peace Symposium in Hamburg, Germany. Nyenemo P. Sanguma, a regional grants officer for The Rotary Foundation who was born and raised in Congo, also sat in, expecting to serve as an interpreter — until Mukwege graciously agreed to conduct the interview in English rather than French.

THE ROTARIAN: You’ve been working on the issue of sexual violence against women in conflict for nearly two decades. But there are still mass rapes, and there are still thousands of women and children coming into your hospital as a result. Is there any reason to think things will improve?

MUKWEGE: Twenty years ago, no one could hear from me. It was taboo to talk about sexual violence, to talk about all these terrible things happening to women. Today I spoke as a keynote speaker about this issue. This is progress.

We have to understand that the world will not change in one day. But I can see that people are starting to really talk about this issue of rape in conflict, and rape generally. Because what is happening in wartime is also what we are living in normal life. In countries like Germany or France, one woman is killed every three days by her boyfriend or her husband, by her ex-boyfriend or ex-husband. Women don’t have the freedom of their bodies, of themselves.

TR: In some parts of the world, women are beginning to speak out about harassment. Are you encouraged?

MUKWEGE: Everywhere I travel, I see women struggling to get the right to be heard. Women are starting to shift the shame from victims to perpetrators. Men will start to think twice before perpetrating rape because they know that women will not keep silent. Silence is a tool that allows rapists to continue. When women keep silent because they may be blamed by police or their own families, it is difficult to have justice. And when a woman keeps silent, another woman will become the next victim.

TR: What needs to happen to effect change?

MUKWEGE: The relationship between men and women should not be a relationship of power and domination. It must be a human relationship, where we are equal. We need to start educating children about this earlier — from the crib. When you start to say this color is for boys and this color is for girls; when you have aggressive things for boys but all the kind things for girls, what are you teaching? We are creating a model where men have to be strong and aggressive, someone with power, to be a man. This has to change to get a world where our children will feel that they are equal so they can support each other.

My dream is to see a world where gender equality can be the general rule. Many of the bad things that are happening are only because men are making a lot of decisions themselves, and most of our decisions are made to get more power, to get more money, to be strong. But this is not the goal. The goal is how we can make decisions together.

TR: How did rape become a weapon of war?

MUKWEGE: We’ve done many studies on this. Rape is performed in war not as a sexual relationship, but as a weapon to destroy. Some of the perpetrators’ methods — raping women with sharp objects; burning or shooting a woman’s genitals — have nothing to do with sex. Rape is a way to terrorize. And it’s really an effective weapon because it’s not only women who are traumatized, but also their husbands and their communities. When men rape 100, 200, 500 women in one night, there must be planning involved. It’s systematic. It was planned to destroy a community.

I have treated women who were more than 80 years old. The first time I treated a 19-month-old baby, I just about lost my patience. How this can happen? When you see those kinds of things, you begin to question human beings. I am starting to get an answer. It’s a kind of terrorism, and terrorism has no humanity. It’s meant to destroy, to harm, and to make things painful for others. And when girls’ genitals are destroyed, it means their capacity to have babies is also destroyed. It’s a form of ethnic cleansing, which is what they did, for example, in Bosnia and Sudan.

TR: Where do you find your inspiration?

MUKWEGE: Most women who arrive at my hospital are completely destroyed, physically and mentally. Living through this terror changes their lives. I’m so surprised to see how these women can stand up and become agents of change in society. Women can be so strong. It pushes me to go on.

TR: You use the terms “victim” and “survivor.” What’s the distinction?

MUKWEGE: Victims are women who come to the hospital with their trauma and feel that nothing will change. But when they overcome that trauma and decide to lead a new life — one where they are not only living for themselves, but working to prevent what has happened to them from happening to others — they become survivors.

TR: Can you give me an example?

MUKWEGE: Every six months we take about 90 young women who went through terrible trauma and put them through a program called City of Joy, which teaches them skills and supports them psychologically. Most of those girls become leaders when they return to their villages. Today, one of them is an anesthesiologist. She told me, “I went through terrible pain, and I don’t want to see other women experience pain.” This is wonderful.

TR: Rotary builds international understanding on a personal basis. Can that be a model for others?

MUKWEGE: What I love about Rotary is how it brings cultures together. When you don’t know another person, you have an impression that he is dangerous to you. This is normal. And when you are afraid, you can do bad things. Rotary’s Youth Exchange is a good thing because when people can cross a culture and see what others are doing, they can change their point of view. I’m sure that if you put people from Africa and from Europe together, there are positive things in each culture that everyone can learn. They can understand each other better, and maybe together build a world better than we have today.

It’s possible, but you can’t do it when you are afraid about the culture of another. When you think that he is not like me, he is different from me, then you can’t build anything positive.

TR: What specific things can Rotarians do?

MUKWEGE: In Rotary, you have a worldwide movement with more than a million people who believe in what they are doing. First, if 1 million members of Rotary said the war in Congo over coltan has to stop, and if they pushed on companies, pushed on international organizations, pushed on the United Nations, it would take only one year before you got a result. Companies and politicians are afraid to have people talk badly about them.

It’s possible to get coltan cleanly, without resulting in the rape of women. The problem is that to get it cleanly, it means that we need to get companies who respect the environment and human beings. But this would cost a little more money. So my cellphone might cost me 10 or 20 percent more, but I would know that it is not harming anyone. It’s my responsibility to say I would rather pay a little more, that I can’t accept that a child be killed because I have to get a cellphone. It’s a social, moral, and ethical responsibility.

Second, in 2010, the UN released a report mapping human rights violations in the Democratic Republic of Congo from 1993 to 2003. It documented that hundreds of thousands of people had been killed. But nothing happened after the report was released. If there is no justice, people feel that they are authorized to do these bad things.

So Rotary clubs need to ask, why can’t we get clean coltan? Why can’t all these atrocities, these crimes against humanity, be prosecuted in Congo? We need people who can demand the implementation of the recommendations [about reparations and legal and security reforms] in the UN report. Rotary clubs can do this. That would make a big difference.

TR: People asked you to run for president of Congo last year. Why did you decline?

MUKWEGE: Residents of Congo have the impression that people become leaders as a way to become rich. When people have this impression, I think, I can’t run for that. What I’m doing is enough for me. I’m a doctor; I’m a teacher. I don’t need more.

TR: So as president, you would no longer be an agent for change?

MUKWEGE: I’m afraid things would remain the same. In Congo, we need a moral revolution. People have to think about how society should be organized. To go on in the same system, nothing will change. We need to work at the grassroots level. People have rights, but they don’t use them. Authorities or leaders should be accountable, but they’re not. How can you be a leader in a country where people don’t understand one another’s roles?

TR: What does justice look like?

MUKWEGE: Justice is not only a repressive tool; it’s also a tool to repair. Justice is a way to fight against repetition. It’s a way to respect the social contract and to guarantee the moral values in society. If you don’t have justice, everyone thinks that they can do what they want and that nothing will happen. We need justice to make people understand, to make people think twice before committing the crime of genocide. TR: What can Rotary do to make that happen? MUKWEGE: Rotary is an organization based on altruism, on trying to make the lives of others better. In Congo, we need to teach people to understand that you can win when you make others win. If you only care about making yourself better, everyone will be worse off. If you make life better for others, your life will be better. So what I can ask Rotarians in Congo to do is to teach others what altruism means.

• Illustration by Viktor Miller Gausa

• This story originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of The Rotarian magazine.

Rotary’s Role

Denis Mukwege’s Panzi Hospital treats an average of 2,000 to 3,000 victims of sexual violence each year; it also provides a wide range of other health services to a regional population of more than 400,000. Rotarians in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in Belgium are helping Panzi serve patients more effectively through a Rotary Foundation global grant project that provided the hospital with a state-of-the-art digital X-ray machine.

“The hospital has been growing so fast over the past 10 years,” says John Peter Mulindwa, a doctor who works in Panzi’s pediatrics and sexual violence programs; he’s also a member of the Rotary Club of Bukavu Mwangaza, the host club for the project. “The flow of patients comes from almost all the provinces within Congo and from neighboring countries. The need became so huge.”

The new machine allows doctors to view results electronically and share them with distant specialists when needed. The rapid results are expected to reduce wait times, which means people get treated more quickly and doctors can see more patients.

The project got its start in January 2017 when Mukwege spoke at a Rotary Foundation seminar sponsored by District 1620 (Belgium). The clubs in attendance donated $120,000 toward the project in response, which was later augmented by $40,000 in District Designated Funds and a grant of nearly $100,000 from the Foundation. The machine was delivered in October 2018 and served more than 1,500 patients in its first eight months.

“Forty-two clubs participated in this huge project,” says Johan De Leeuw, the district Rotary Foundation chair at the time. “I am very proud of that.” De Leeuw is already working with Mukwege on another humanitarian project.